The Battle of the Sexes: The Fight for Gender Equality in Sports

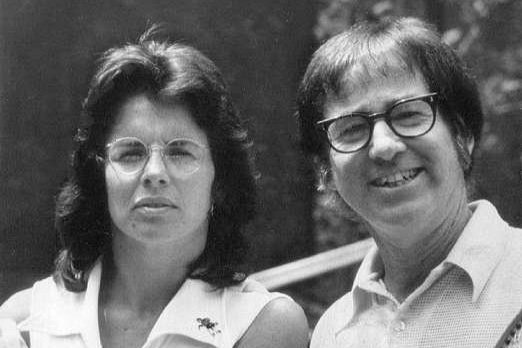

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On the evening of September 20th, 1973, over 30 thousand spectators filed into the Houston Astrodome, and another 90 million people were tuned in on television to watch one of the most iconic and polarizing spectacles in sports history: The Battle of the Sexes. This tennis match was a face off between 29-year-old Billie Jean King, widely viewed as the best female tennis pro of the time, and 55-year-old Bobby Riggs, a retired pro who was once the best in the world. While King and Riggs were both talented tennis players, this match was about far more than just tennis. Not only was it the most viewed sporting event of the 1970s, but it also symbolized broader societal conflict over gender roles, equality, and women’s legitimacy in professional sports. The event became a cultural phenomenon, amplified by media narratives that pitted King’s feminist ideals against Riggs’ self-proclaimed chauvinism. This paper seeks to explore the media’s role in shaping public perception of the match and its broader implications for women’s sports. Specifically, it asks: How did pre-match coverage frame King and Riggs in terms of gender stereotypes and societal expectations? How did post-match reactions influence public attitudes toward female athletes and women’s tennis? Finally, how has the legacy of the match shaped discussions about equity and representation in sports? I will argue that while the media often reinforced reductive gender stereotypes in framing the Battle of the Sexes, Billie Jean King’s victory disrupted these narratives, serving as a catalyst for greater visibility and credibility for women’s sports, even as long-standing inequalities persisted. Through an analysis of live coverage, commentary, and retrospective narratives, this paper examines the complex ways the match reflected and reshaped cultural attitudes toward gender and athletics.

Prior to the Battle of the Sexes, female athletes were given a fraction of the respect and attention as their male counterparts, and much of the general public did not believe that women even belonged in the sports world to begin with. These sexist beliefs were deeply rooted in societal norms that undermined their athletic abilities and brought into question their femininity. Athleticism was historically associated with qualities deemed masculine– strength, aggression, and competitiveness– leading to the perception that successful women in sports were deviating from traditional feminine ideals and conventional womanhood. This deviation often invited accusations of “mannishness,” a term weaponized to label women who presented with athletic characteristics, ones that were solely reserved for men at the time. For male athletes, the media focus was on their strength, speed and skill, while the focus for female athletes was on their appearance, with journalists emphasizing attractiveness and diminishing their achievements. Journalists of the time would “attack the mannish athlete as ugly and sexually unappealing, possibly deficient,” reflecting broader anxieties about gender and sexuality. This led to a widespread fear that female athletes would “inevitably acquire masculine sexual characteristics and interests,” hence would be considered lesbians. At this point in history, mannishness and lesbianism went hand in hand for female athletes, and conversations surrounding female athlete’s sexualities were not rare. The stereotype of the lesbian athlete emerged as a way to marginalize and stigmatize women who visibly challenged gender norms in their sport, particularly in a cultural moment when feminism and the LGBTQ+ rights movement were gaining prominence. This cultural hostility was not confined to sports alone but reflected a broader societal contempt for women who stepped outside prescribed roles with the historian Susan Cahn writing, “especially during the hard years of the depression, a hostile public expressed its open contempt for feminists, career women, working wives, and lesbians.” Within this context, the stereotype of the lesbian athlete became a means of enforcing conformity, deterring women from fully embracing their potential in sports and perpetuating the idea that athletic success came at the expense of femininity and social acceptance.

Billie Jean King, an unparalleled athlete and advocate for gender equity, became a focal point in this cultural dynamic. King avoided public discussions of her sexuality during this period, aware of the societal risks it posed to her career and advocacy, while in fact being married to a man at the time. Despite this, her dominance on the court and leadership in the women’s movement made her a figurehead for debates about gender and sports. Billie Jean King writes in her recent autobiography, All In, “I became a symbol for people who were tired of seeing women dismissed en masse, demeaned as second-class citizens and shut out of opportunities everywhere, not just sports.” As feminism pushed for expanded roles for women in public life, King’s ability to challenge perceptions of female athletes without alienating the mainstream was pivotal.

The efforts towards gender equality in sports began long before 1973, although the Battle of the Sexes was a significant inflection point in the movement. Milestones such as the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, granting women the right to vote, laid the societal foundation for equality across all sectors, including sports. In 1963, Betty Friedan published her book, The Feminine Mystique, documenting the emotional and intellectual oppression that middle-class educated women faced due to limited life options. This work helped mobilize the modern feminist movement and underscored the need for systemic change. During the 1940s and World War II, the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League became the first women’s professional sports league. Although the league imposed strict standards on women, it represented a radical and significant step forward for women’s participation in professional sports. All of these events preceded the “Battle of the Sexes” and laid the groundwork for the propulsion of the women's movement in sports.

King had also been active in this women’s movement prior to 1973. In 1970, Billie Jean King and eight other female tennis players, famously known as the “Original 9,” created their own national tour known as the Virginia Slims Tour, in response to the governing bodies trying to keep women out of Grand Slam tournaments. The tour’s success and popularity not only proved the viability of women’s tennis as a professional sport but also paved the way for the establishment of the Women’s Tennis Association in 1973, with King as its founder. These efforts laid the groundwork for the fight for equal prize money, underscoring her role as both a revolutionary athlete and a force for systemic change. By 1971, Billie Jean King became the first female athlete to earn more than $100,000. In 1972, both Title IX and the Equal Rights Amendment were passed which cemented the idea of equal opportunities for men and women and outlawed discrimination on the basis of sex. The same year, Ms. Magazine launched as the first American feminist magazine. Yet, even with these strides, media coverage often reflected the prevailing cultural biases: King’s designation as Sports Illustrated’s “Sportsperson of the Year” in 1972 was groundbreaking, but she was forced to share the cover with a male athlete, diluting the acknowledgment of her singular accomplishments. King became a bridge between the rising feminist movement and a society still hesitant to embrace women’s equality. The cultural battle surrounding these perceptions set the stage for the symbolic power of her victory in the Battle of the Sexes. King personified both the progress of the women’s movement and its tensions, using her platform to normalize women’s athletic success and to break down the stereotypes that framed strength, independence, and athleticism as inherently unfeminine.

Bobby Riggs was the antithesis of what Billie Jean King was fighting for, as a self-proclaimed male-chauvinist and a vocal critic of women’s sports. At a pre-event press conference, Riggs repeatedly claimed that the women’s game was inherently inferior to the men’s. However, Riggs was not merely a provocateur; he was a showman, an opportunist, and more than all a hustler. A former tennis champion with undeniable talent; his career had shifted to one defined by attention-seeking antics and gambling exploits. Riggs’ persona made him a compelling yet controversial figure, one who thrived on spectacle and would go to any lengths for publicity or profit. This combined with his ability to draw massive crowds, made him the perfect matchup for King in what would become a larger fight over women’s rights that the Battle of the Sexes represented. He had challenged King to a match once before, but she declined, wary of the potential consequences of losing in a cultural climate already skeptical of women’s sports. This left him to face off with Margaret Court, the top female player in the world. Court lost to Riggs, in what is now known as the “Mother’s Day Massacre,” which prompted Billie Jean King to accept the earlier offer. She believed that under the intense pressure and scrutiny surrounding the event, she could prove herself and deliver a victory that would resonate far beyond the tennis court.

Leading up to the match, the media framing was very divisive, obviously pitting men against women, and broadcasters perpetuating the sexist agenda. The “Battle of the Sexes” as a broadcast event was unlike anything seen before. Aired on ABC Sports, and announced by Howard Cosell, Rosemary Casals, and Gene Scott, they garnered the most viewers of a tennis match in history. Jack Kramer was supposed to be announcing on the broadcast as well, until Billie Jean King threatened to pull out of the match unless ABC replaced him. She said, "He doesn't believe in women's tennis. Why should he be part of this match? He doesn't believe in half of the match. I'm not playing. Either he goes—or I go." He was then replaced by Gene Scott. Casals was a friend of King and an outspoken women's rights advocate. They relied on the dichotomy of Casals’ and Scott’s commentary throughout the match to spark conversation, meanwhile Riggs leaned into his persona with comments designed to provoke outrage and generate attention. In a pre match interview he said, “the male is king, the male is supreme. I’ve said it over and over again. I still feel that way. Girls play a nice game of tennis for girls, but when they get out there on a court with a man, even a tired old man of 55, they’re going to be in big trouble.” His brash statements including a statement that he likes women “in the bedroom and the kitchen,” and that the “best way to handle the women is to keep them pregnant and barefoot,” framed him as the embodiment of patriarchal attitudes that King sought to dismantle. He was not the person at this match who was openly critical of women. In a courtside, pre match interview, famous fashion designer, Oleg Cassini said, “There is no way a good woman could beat a fairly good man.” These statements not only heightened the stakes of the match but also amplified its symbolic resonance as a confrontation between traditional gender roles and the push for equality.

The commentary during the match continued to reflect these biases, often belittling King’s capabilities, despite her proven athletic dominance. Male announcers reinforced traditional femininity standards with remarks about her appearance saying “King always looks like a very attractive young lady and sometimes you get the feeling that if she ever let her hair grow down to her shoulders and took her glasses off you'd have somebody vying for a Hollywood screen test.” Simultaneously, her athletic abilities were undermined by assertions from male announcers that “as all women, she may be a little bit slower than the men,” once again perpetuating stereotypes about female inferiority in physical competition.The conversations during live coverage thus framed the match as both a sporting event and a battleground for sexist assumptions, casting Riggs as the favorite while subtly questioning King’s legitimacy, with the only pushback coming from Casals. However, this framing also set the stage for the significance of her eventual victory, transforming the event into a symbolic win over these outdated biases.

As history would have it, Billie Jean King took home the prize money, blowing Riggs out of the water in a 6-4, 6-3, 6-3 victory. The mainstream media was quick to celebrate this win, and shifted their narrative to be incredibly positive towards King, with little critique of her following the match. The following day, The New York Times, for example, wrote, “ she convinced skeptics that a female athlete can survive pressure-filled situations and that men are as susceptible to nerves as women.” Billie Jean King’s victory over Bobby Riggs was viewed as a victory for all women and sparked a wave of media attention that reflected the weight of the moment and its implications for women’s sports. Many feminist outlets including Lavender Woman also celebrated it as a historic triumph for women with headlines like “Billie Jean King defeats Bobby What’s-His-Name” and “a long hard cheer for Billie Jean King who has come a long way to reclaim tennis — introduced into this country by women — for women.” Of course, there was some skepticism that followed her victory as well, with people questioning if the match was thrown, or simply a money-grab that would leave no lasting impact or improvement to womens sports. Feminist critiques of the event and its framing were also quite nuanced. While some did not agree with King’s participation in a match filled with sexist motivations and sensationalism, others noted that her skill and composure ultimately trumped Riggs’ persona and the reductive media narratives. Following the match, the popular Seattle feminist magazine, Pandora, wrote “It was pretty awful to see Billie Jean King going along with the whole thing, but during the match it became evident that her excellence in the sport was more important than any amount of psyching out or carrying on. It will be quite a while until the media gives any serious coverage to women's sports.” They acknowledged that the event brought significant attention to women’s sports, boosting morale and creating minor but meaningful steps toward equality. Billie Jean King herself recognized this duality, stating that women’s tennis never claimed superiority over men’s but sought equal recognition for its entertainment value. In King’s own words, “If one can see beyond the more immediate sexist motivations and commentary, Bobby Riggs will be doing women’s sports an unintended favor,” referring to the match’s global reach and anticipated impact.

King’s dominance during the match proved the legitimacy of women’s athleticism, forcing audiences to rethink stereotypes about female athletes’ inferiority. Yet, as one observer remarked, it would still “be quite a while until the media gives any serious coverage to women’s sports.” As King herself acknowledged, the event brought unprecedented publicity to women’s tennis but left the larger question of whether this attention would endure. Margaret Paul wrote in Pandora magazine in 1973, “publicity is publicity and women’s tennis is getting more of it. Whether the entertainment value of women’s tennis for the general public will experience a lasting increase because of this publicity, remains to be seen.” This skepticism reflected the reality that while the match boosted visibility, it did not dismantle the structural inequalities female athletes faced. It gathered eyes and initiated commentary, yet there was a lack of immediate, systemic change following King’s victory. The growth and progress in women’s sports were beginning to move forward, just at a very slow pace. For instance, Billie Jean King went on to create WomenSports Magazine shortly after her win to address the glaring lack of women’s coverage in mainstream publications like Sports Illustrated, when King was not even featured in the October edition. Conversely, after Riggs beat Margaret Court, the front page of Sports Illustrated read “Never bet against this man,” with a full sized photo of Riggs. Two years after the match, Sharon Haywood wrote in Pandora magazine, “Ever since Billie Jean King so successfully batted Bobby’s balls around on network television, TV seems to be taking somewhat more of an interest in women’s sports.” Although the progress was slow, the event was a moment in history and helped gain momentum for third-wave feminism across the United States for women’s sports.

In conclusion, the Battle of the Sexes was far more than a tennis match, it was a cultural moment that represented the tensions and aspirations of its time. Billie Jean King’s victory over Bobby Riggs symbolized a triumph over the widespread sexism that had long belittled women’s capabilities in sports and beyond. It offered a glimpse of the potential for greater equality in sports and society. While the event itself did not dismantle the structural barriers faced by women in sports, it brought unprecedented attention to female athletes and initiated a national conversation about their legitimacy and place in sports. The legacy of the Battle of the Sexes lies not just in King’s win, but in its role as a catalyst, a moment that brought gender inequality in sports to the forefront of public discourse. While the path toward equality remains incomplete, the match served as a powerful reminder of the resilience and potential of female athletes, inspiring generations to continue pushing for progress on and off the court. King's grace under pressure and undeniable talent transformed the spectacle into a statement of empowerment, even as media coverage and societal perceptions continued to lag behind. King’s victory remains a powerful reminder of the importance of visibility, determination, and collective action in the ongoing journey toward equity. Even today there are remaining gender inequities in sports, but the progress, especially in recent years, has been incredible. There is still progress to be made, but overall society has come a long way since The Battle of the Sexes.

Sources:

“AAGPBL League History.” AAGPBL League History. https://www.aagpbl.org/history/league-history.

Amdur, Neil. “Mrs. King Defeats Riggs, 6-4, 6-3, 6-3, Amid a Circus Atmosphere.” The New York Times, September 21, 1973, Late City edition.

“Battle of the Sexes (Tennis).” Wikipedia, September 28, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Sexes_(tennis)#:~:text=Her%20intention%20was%20to%20deny,in%20half%20of%20the%20match.

Cahn, Susan K. Coming on strong: Gender and sexuality in Women’s Sport. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Haywood, Sharon. “TV Wakes up to Women’s Sports.” Pandora. January 22, 1974, 4 edition, sec. 8.

Jentsch, Eric W. “Beyond the Court: Billie Jean King’s Triumph in the Battle of the Sexes | Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum.” Smithsonian American Women’s History, September 13, 2023. https://womenshistory.si.edu/blog/beyond-court-billie-jean-kings-triumph-battle-sexes.

King, Billie Jean, Johnette Howard, and Maryanne Vollers. All In: An Autobiography. DoubleDay Publishing Group, 2021.

Lavender Woman Collective. “Feminist Tennis.” Lavender Woman. October 1973, 2 edition, sec. 6.

maxine. “Are Women Good Sports?” Off Our Backs. October 1973, 3 edition, sec. 11.

Paul, Margaret. “Analyzing a Famous Match.” Pandora 3, no. 17 (May 29, 1973): 3–3

Sweeney, Sarah. “Appreciating Billie Jean King’s Contribution to Second-Wave Feminism.” Harvard Gazette, November 20, 2008. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2008/11/appreciating-billie-jean-kings-contribution-to-second-wave-feminism/.

“Tennis Battle of the Sexes Special (September 20, 1973).” YouTube, August 31, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qqB3yi8MVbQ.

Wind, Herbert Warren. Game, set, and match. Open Road Media, 2016.

Wong, Ethan. “The ‘Battle of the Sexes’: An Embodiment of Gender Conflicts in the 1970s and Influence on Equality in Sports.” Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media 4, no. 1 (May 17, 2023): 470–75. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-7048/4/2022130.

Newton, Esther. “The Mythic Mannish Lesbian: Radclyffe Hall and the New Woman (1984).” Margaret Mead Made Me Gay, December 31, 2020, 176–88. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822381341-016.